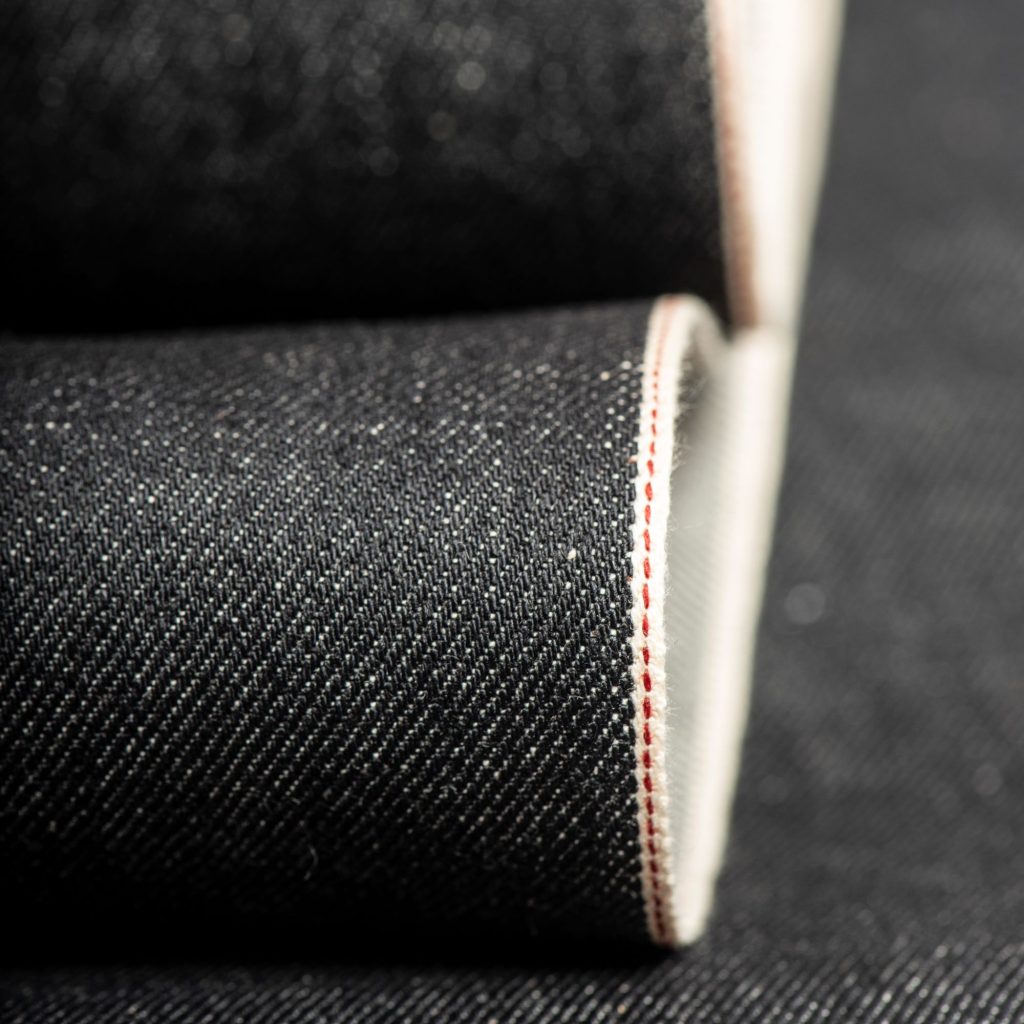

When most people hear “selvedge,” they think of denim. A narrow strip along the seam, often with a colored thread, used by brands to signal heritage or authenticity. But selvedge is much older and more widespread than denim. It is not just a construction detail but a principle — a way of weaving that says something about how cloth is made, and what values stand behind it.

At its core, selvedge is a story about edges. About how you choose to finish something, and what that decision communicates. In textiles, as in design, finishing matters — it defines whether something feels temporary or permanent, disposable or intentional.

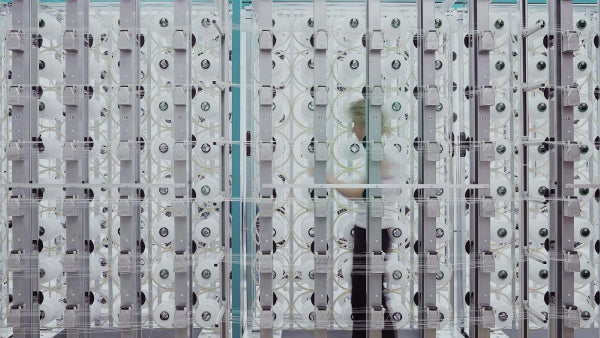

The word “selvedge” comes from “self-edge.” On a shuttle loom, the weft yarn carries across the fabric and loops back, binding the edge in one continuous motion. This creates a tight, self-finished border that doesn’t fray. No overlocking. No reinforcement. The loom itself produces a clean, durable edge.

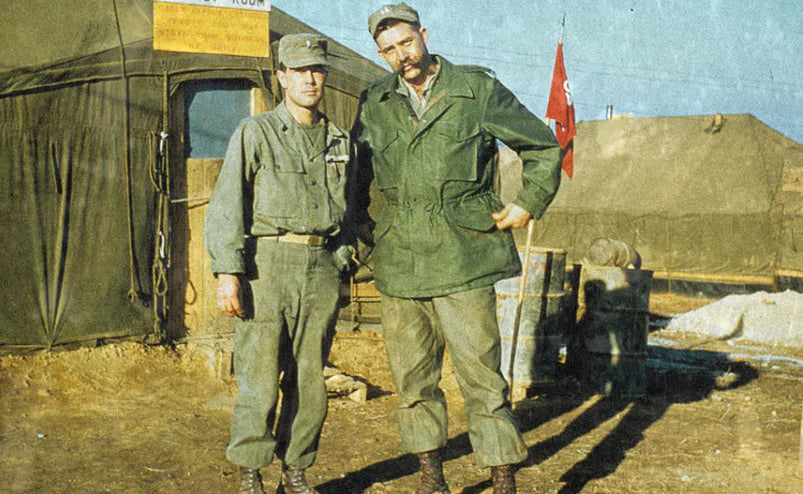

This was once the norm. Before denim ever entered the picture, selvedge defined cloth across continents. In Europe, wool broadcloth for tailoring and military uniforms was valued for its neat selvedge edges. In Asia, silk shawls and ribbons used selvedge both for durability and as a visible mark of refinement. In early America, canvas sails, cotton duck for tents, and ticking for bedding were woven narrow with selvedge edges, chosen for strength and longevity rather than style.

Across all of these uses, the meaning was consistent: selvedge was a sign of care. It showed that fabric had been made with precision, not speed. It was proof that the cloth could withstand wear, handling, and time.

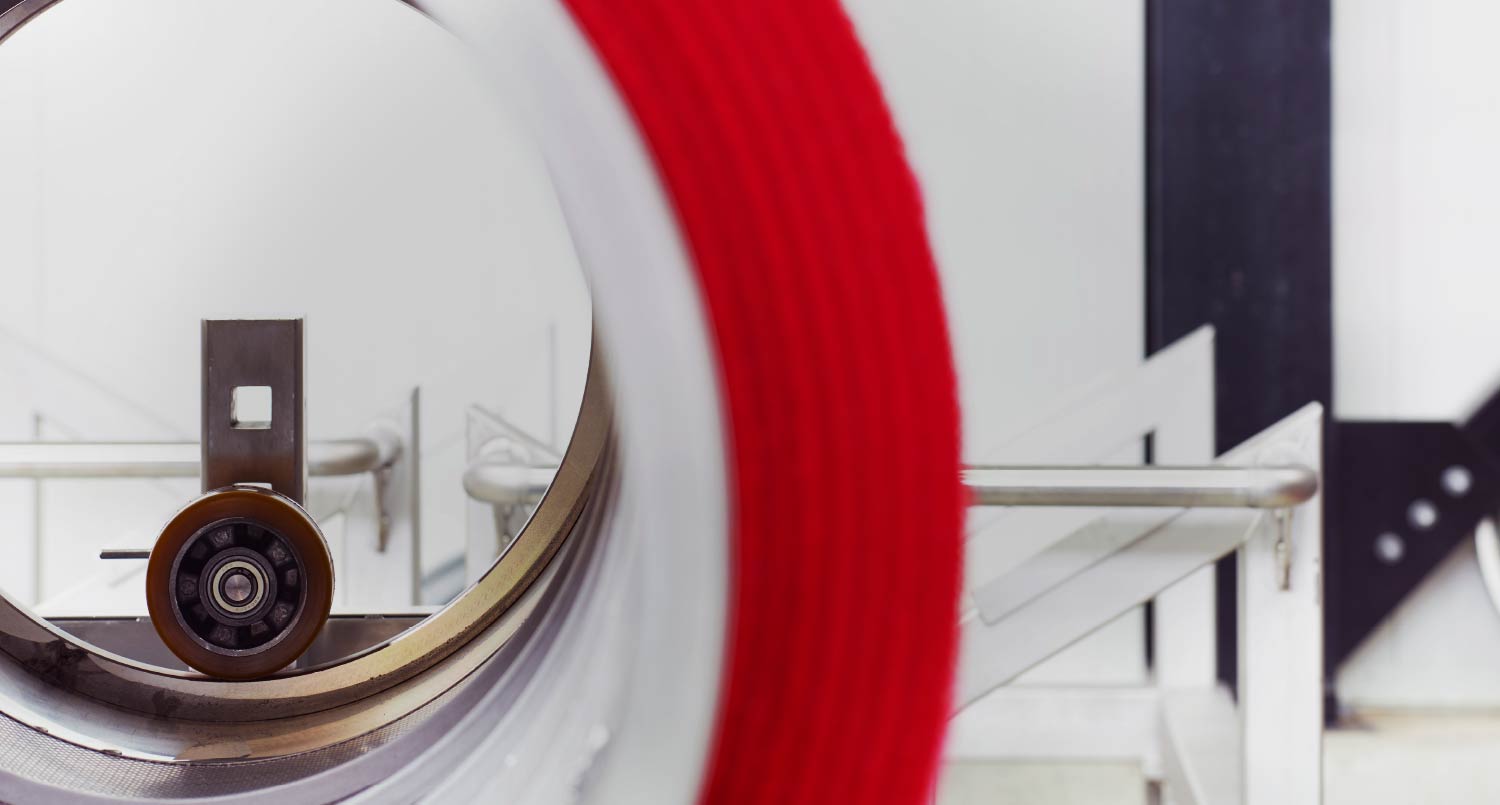

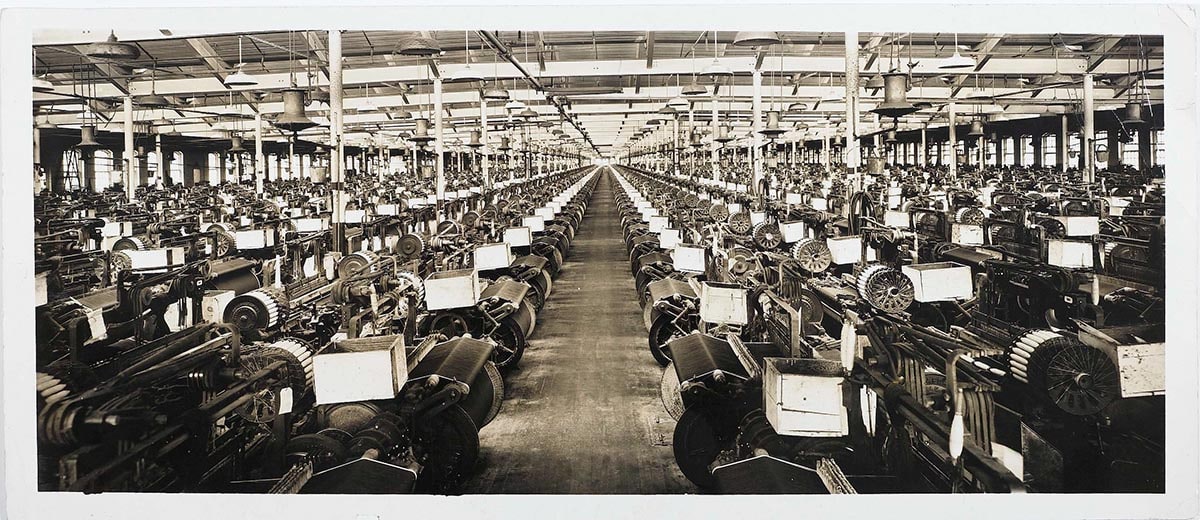

Selvedge began to fade in the 20th century — not because it stopped working, but because economics changed. Shuttle looms were narrow and relatively slow. They produced fabric about 28–32 inches wide, and each pass of the shuttle took time. As global demand for textiles surged, mills needed output, efficiency, and width.

Projectile, rapier, and later air-jet looms solved this. They could weave cloth 60 inches or wider, at much higher speeds. But these modern looms cut the weft yarn at each pass, leaving raw edges that had to be bound later with stitching or overlocking. The cloth functioned the same in use, but the woven edge — the built-in guarantee — was gone.

This trade-off was rational for industry. More fabric per hour meant lower costs and greater accessibility. But something subtle was lost: the idea that the edge itself held meaning. Selvedge was precision. Mass production was speed. The choice between them wasn’t just mechanical — it reflected priorities about what was valued.

When selvedge edges disappeared from most textiles, the difference wasn’t obvious to the average consumer. Clothes still fit. Canvas still held. Fabrics were cheaper, more widely available, and good enough for their purpose. For everyday use, it seemed like progress.

But for those who worked with cloth — tailors, seamstresses, collectors, and designers — the absence was clear. The selvedge edge had been a built-in assurance: a detail that quietly told you the fabric was deliberate, that time had been taken. Without it, cloth became a commodity: undifferentiated, efficient, and stripped of a certain depth of meaning.

Selvedge didn’t disappear entirely. Specialty mills in Japan and small groups of makers preserved old shuttle looms and continued weaving with them. For these communities, the selvedge edge wasn’t just functional — it was symbolic. It represented continuity, resistance to disposability, and a respect for methods that took more time but produced something more enduring.

In the late 20th century and into today, selvedge returned as a cultural marker. It wasn’t revived because the world needed it — but because people valued what it represented. Selvedge edges became a visible signal of authenticity, of a slower way of making. It turned from a technical detail into a cultural code.

Selvedge now exists in tension with modern production. On one hand, most textiles are still produced on wide, high-speed looms — efficient, affordable, and necessary for global demand. On the other, selvedge edges live on as a counterpoint: a reminder that scarcity, precision, and permanence still matter.

This is why selvedge resonates today. It represents a choice. It’s scarcity in a world of abundance, patience in a culture of urgency, and authenticity in an economy built on scale. Selvedge shows that even the smallest edge can carry meaning — not just in cloth, but in the values we bring to making.

At Foehn, details like selvedge remind us that textiles are never neutral. They reflect choices about production, values, and philosophy. Do we prioritize speed, or precision? Do we produce more, or do we build with care?

Selvedge may seem like a minor detail, but it speaks loudly. It’s proof that the edge of a fabric can tell a story about culture, economy, and craft. And it reminds us that how something is finished often says everything about what it stands for.