When World War II ended, a generation of veterans returned home with mountain skills earned on the glaciers of Europe and in the alpine battles of northern Italy. In the U.S., the 10th Mountain Division had trained for warfare in snow and cold — and came back knowing firsthand what worked in the mountains, and what didn’t. But the gear they needed didn’t exist.

In the late 1940s, outdoor equipment was crude: cotton sleeping bags, leaky canvas tents, and heavy rucksacks with leather straps. European makers like Grivel and Salewa were innovating, but their gear was slow to reach North America. Yet everywhere, there was a hunger for the outdoors — a postwar longing for space, freedom, and challenge.

Into this gap stepped the first American gear pioneers: Gerry Cunningham, Roy and Alice Holubar, and Dick Kelty. They weren’t chasing markets — they were solving problems. Cunningham reimagined tents and hardware. The Holubars sewed lighter, warmer sleeping bags and alpine parkas. Kelty’s external-frame backpacks changed how people carried weight in the backcountry.

Together, they didn’t just build better gear. They built the foundation of a new industry.

Holubar

In Boulder, Colorado, Roy and Alice Holubar were thinking about how to make better gear for themselves and their friends in Colorado Mountain Rescue — many of them 10th Mountain Division veterans who had stayed out West after the war.

The first breakthrough came by sewing lightweight down sleeping bags out of surplus parachute nylon. These were radical at the time — warm, compressible, and light enough to haul deep into the backcountry. While most American outdoor gear was still stuck in canvas and cotton, Alice was already experimenting with high-performance fabrics.

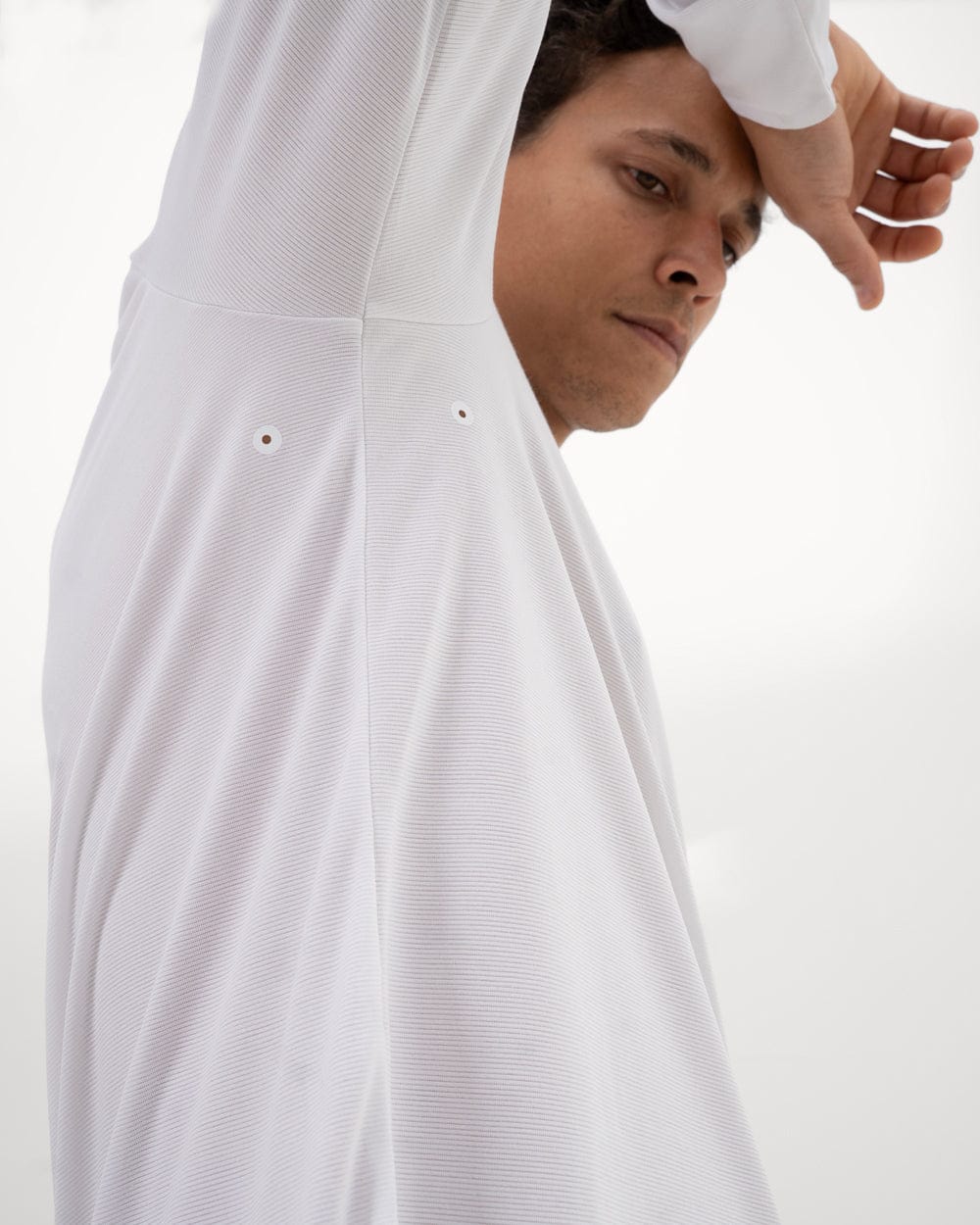

Sleeping bags were just the beginning, Alice and Roy went on to develop the Holubar Mountain Parka, one of the first serious attempts at breathable, weather-resistant outerwear for alpine environments. Their use of NP-22, a nylon-pima cotton blend, predated the now-iconic 60/40 cloth by more than a decade. Designed for ruggedness and breathability, NP-22 quickly became the standard issue for Colorado Mountain Rescue — its performance tested in real-world alpine conditions long before “technical outerwear” was a category.

Holubar didn’t stop at design. They also pioneered DIY Carikits, giving customers the tools and instructions to sew their own parkas, sleeping bags, and tents at home — one of the first true direct-to-consumer concepts in outdoor gear.

The multi-pocketed parka, the V-baffle sleeping bag, the idea that gear could be made at home — Holubar helped define what outdoor equipment could be.

GERRY Mountain Sports

In Ward, Colorado, Gerry Cunningham was asking the same questions, but with a different eye. Where Holubar pushed the envelope on insulation and outerwear, Cunningham looked at the nuts and bolts: How could the pack work better? How could the hardware be lighter, simpler, smarter?

In 1938, before the war interrupted his plans, Cunningham had already prototyped a backpack that used zippered closures instead of the traditional flap-and-buckle design. After the war, when he officially launched GERRY Mountain Sports in 1946, that same spirit of engineering ingenuity ran through everything, all the backpacks, tents, and outerwear he made.

His list of firsts reads like a blueprint for modern gear:

• Triangular carabiner (1950): A radical improvement on traditional hardware, reshaping what climbers clipped into.

• The drawstring clamp (cord lock): That tiny spring-loaded toggle you still find on every backpack and sleeping bag today? Gerry invented it.

• The Gerry Kiddie Carrier: The first aluminum-framed child backpack carrier, patented in 1963. Still a familiar sight on trails around the world.

• The Gerry Squeeze Tube (1955): A refillable tube for foods like peanut butter and jelly — one of the earliest examples of lightweight, reusable food storage for backpackers.

But Cunningham wasn’t just solving gear problems — he was teaching people how to use gear better. His free educational booklets, like How to Keep Warm and How to Camp and Leave No Trace, helped define the ethics and techniques of backcountry travel for an entire generation. His now-famous advice — “If your feet are cold, put your hat on” — is still repeated today.

Gerry Cunningham didn’t just make better gear. He gave people the knowledge to use it well.

Kelty

While Holubar was rethinking insulation and GERRY was reinventing the hardware, Dick Kelty was solving one of the most fundamental challenges of the outdoors: how to carry the load.

In the early 1950s, Kelty — a carpenter by trade and a backpacker by passion — began building external-frame packs in his Southern California garage. He wasn’t the first to put a wooden frame behind a rucksack, but his breakthrough was in materials and execution. By replacing heavy wooden frames with welded aluminum tubing and pairing them with contoured shoulder straps and a proper hip belt, Kelty created a pack that could carry serious weight comfortably over long distances — a revolution for multi-day backcountry travel.

Just as Holubar’s down bags and GERRY’s gear made the mountains more survivable, Kelty’s packs made them more reachable. His designs were used on some of the biggest expeditions of the era, including the 1963 American Everest Expedition, but they were also embraced by everyday hikers and backpackers. Kelty’s genius wasn’t just in reducing weight — it was in making good design accessible, building packs that worked for families, scouts, and weekend adventurers, not just elite climbers.

For many, a Kelty pack was their first real piece of technical outdoor gear. Affordable, repairable, and built to last, Kelty’s packs helped define the backpacking boom of the 1960s and ’70s — not as a sport for experts, but as a way for anyone to experience the backcountry.

Kelty didn’t invent the backpack. He made it work for the people who needed it most.

The Web of Influence

The story of Holubar, GERRY, and Kelty isn’t just about who made what first. It’s about how good ideas spread.

The most important innovations of this first wave didn’t stay locked inside catalog pages or workshop walls. They traveled — from maker to maker, from climber to climber, from one cold night in the mountains to the next. Passed along through friendships, shared expeditions, gear swapped between hands, and quiet observation at the trailhead or on the rope team. Knowledge moved by necessity. Good design moved because it worked.

Holubar, GERRY, and Kelty weren’t building an industry. They were solving problems — warmth, weight, fit, function. But in doing so, they created the blueprint that others would follow.

Holubar’s approach to insulation, outerwear, and DIY kits shaped the thinking of the next generation of designers. Bob Swanson and George Marks, both veterans of early North Face and Trailwise, took those lessons forward when they co-founded Sierra Designs in 1965. Their take on the 60/40 parka became a standard, and their tents and sleeping bags helped bring lightweight gear to a broader audience.

Jack Stephenson’s Warmlite pushed the ideas even further. After a miserable 1955 honeymoon — ruined by bad gear and rescued by an introduction to the Holubars — Stephenson returned home determined to do better. His answer was radical: ultralight down bags, vapor barrier systems, and single-wall tents, all engineered through the precise lens of thermodynamics. Long before “ultralight” was a word, Stephenson was defining the concept.

And while that thread of influence wove through Boulder and Berkeley, Dick Kelty’s breakthrough on the West Coast carried the same spirit. His welded aluminum-frame packs redefined how people moved through the backcountry — not just climbers, but scouts, families, and first-time backpackers. Kelty’s designs helped democratize access to the outdoors, proving that good gear could make the experience possible for more people, not just experts.

These weren’t isolated inventions. They were part of a shared momentum — a rising belief that the right equipment could change what was possible in the mountains.