Plain weave is the simplest, most fundamental way to transform thread into cloth. In this structure, warp and weft interlace in an alternating over-under rhythm, creating a balanced crisscross grid. It is known by many names — tabby, one-up-one-down, linen weave — but the essence is the same.

This simplicity gave it endurance. Archaeologists have found plain-weave imprints in Ice Age clay, woven flax in Neolithic villages, and finely finished linen in Egyptian tombs. Across thousands of years and all corners of the globe, plain weave provided not just clothing but symbols, currency, sails, and ritual objects. It is no exaggeration to say the plain weave is the backbone of textile history — a structure so straightforward that it has outlasted empires, industries, and even revolutions in material science.

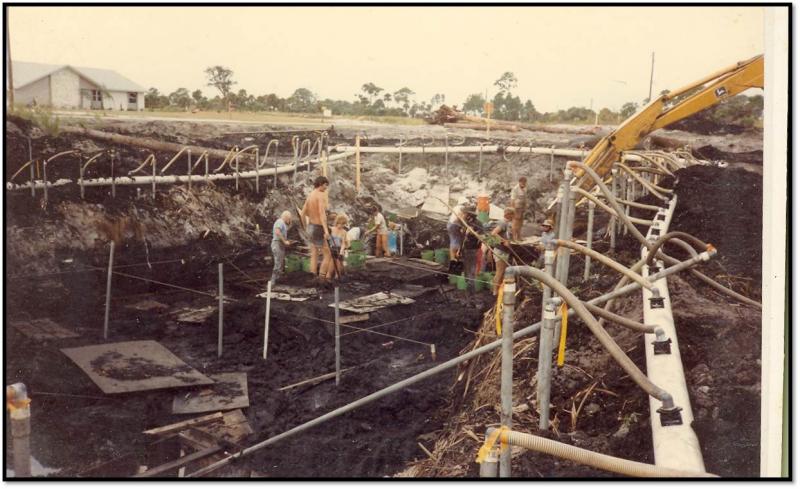

Windover site in Florida, the oldest preserved flexible fabric in North America was discovered here.

The earliest evidence of weaving stretches back some 27,000 years, with clay fragments from Dolní Věstonice in the Czech Republic showing impressions of what was almost certainly plain weave.

Similar traces appear across the globe: plant-fiber fabrics at Florida’s Windover site (6000–5000 BCE), woven cordage from Peru’s Guitarrero Cave (~9000 BCE), and Neolithic flax fragments from Çatalhöyük (~7000 BCE) and Egypt’s Fayum (~5000 BCE). By this time, weaving had become widespread, with flax cloth even found in Swiss lake dwellings — proof that plain weave’s simplicity, stability, and versatility made it the default method wherever yarns were spun.

Plain weave was the common denominator across the world’s first great civilizations, but it was never just cloth. Each society wove it from different fibers, adapted it to climate and resources, and gave it meaning that stretched far beyond utility.

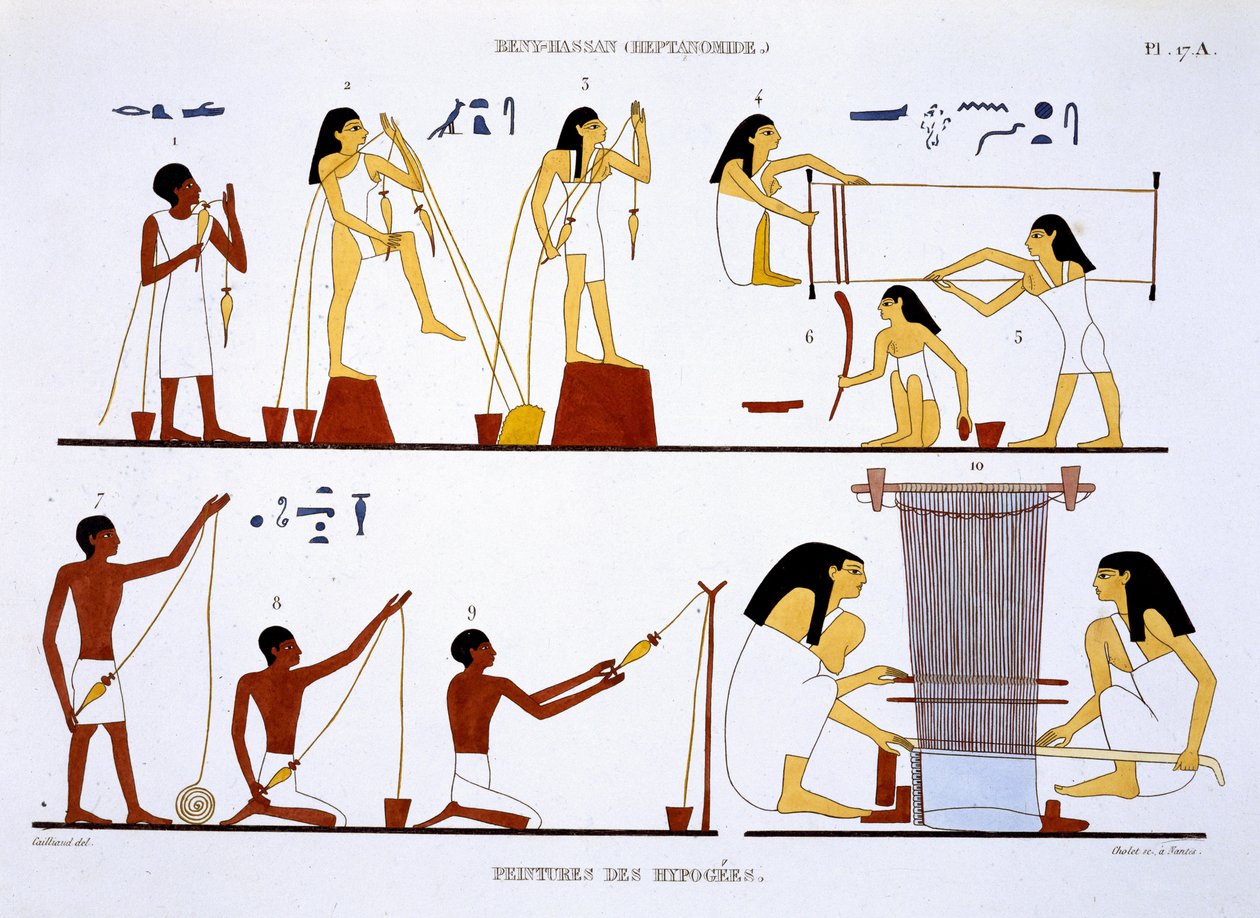

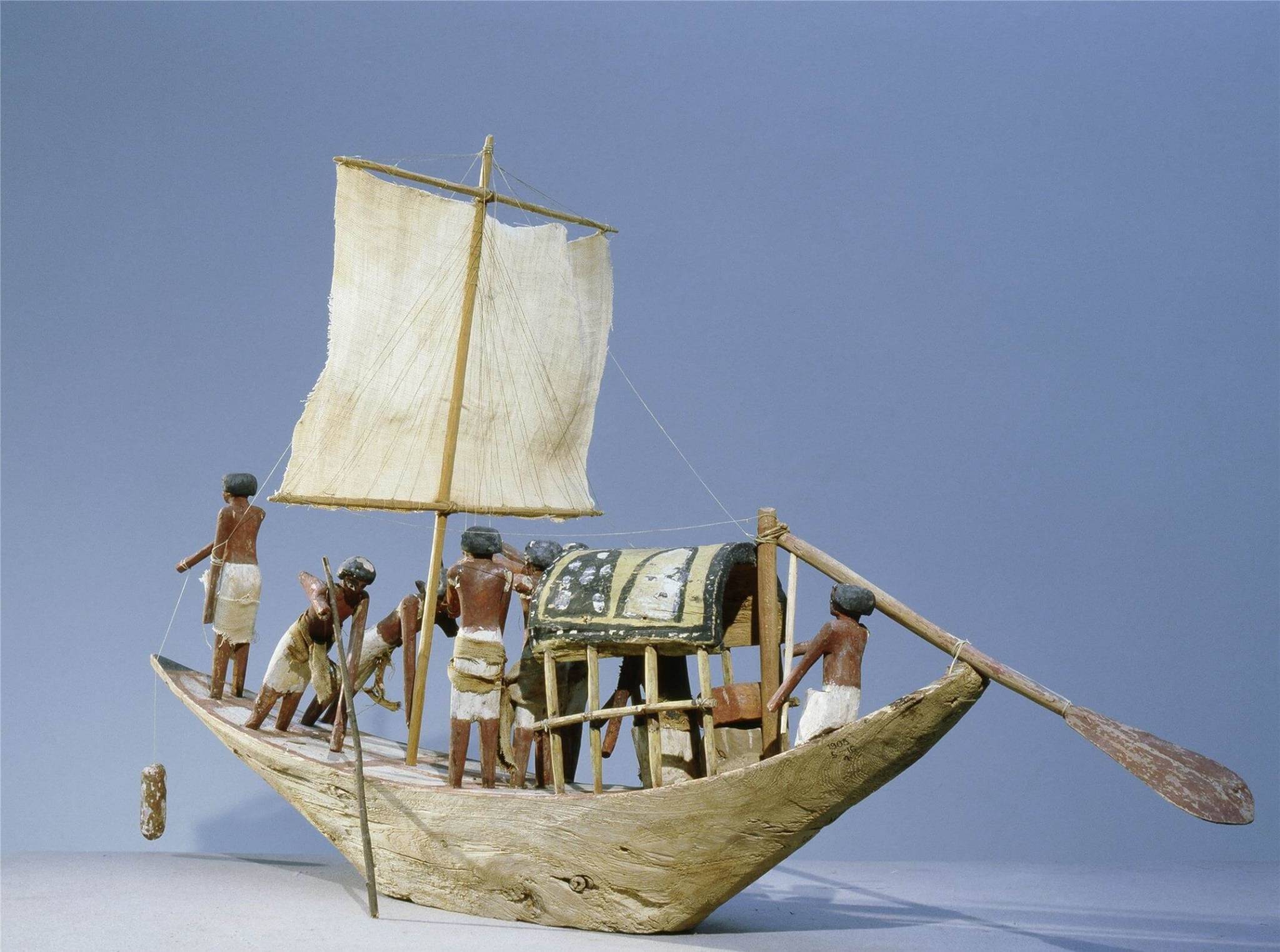

Egypt’s flax fields made linen the fabric of daily life and eternity. By 3000 BCE, weavers produced plain-weave cloth so fine it clothed pharaohs, priests, and farmers alike. Linen embodied purity, which made it central to ritual: it wrapped mummies, dressed temple statues, and was burned as sacred offering. At the same time, bolts of linen functioned as a medium of exchange, recorded in temple accounts and tax records. Its association with both economic value and spiritual symbolism ensured linen’s dominance in Egypt for millennia.

In Sumer and Babylon, sheep provided the fiber that clothed an empire. By the 3rd millennium BCE, wool plain weaves were the staple fabric. Temple workshops employed thousands of women spinning and weaving, producing cloth as tribute, tax, and trade commodity. Linen was known, but scarce, reserved for high status or ritual contexts. Everyday garments, from the kaunakes skirt to wrapped tunics, were plain-woven wool. Weaving’s centrality was reinforced in myth: Uttu, goddess of weaving, ensured that the loom itself carried divine weight. Wool plain weaves were both the workwear of commoners and the currency of empire.

The Indus Valley civilization domesticated cotton around 3000 BCE, making India the birthplace of cotton weaving. Plain-weave muslins and calicos were lightweight, breathable, and strong — ideal for hot climates. Over centuries, Indian cotton spread outward, astonishing Greeks and Romans with its fineness. By the early modern era, those same plain-weave cottons became global commodities, flooding European markets and sparking colonial industries. What began as local cloth became the foundation of global trade networks, proof that plain weave could be both humble and world-shaping.

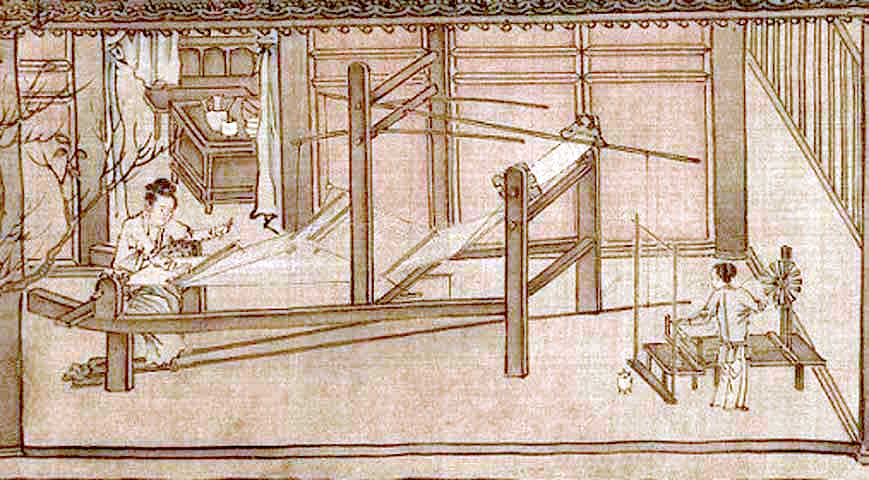

Legend attributes silk’s discovery to Lady Hsi-Ling-Shih around 2700 BCE. By the Shang dynasty (~1300 BCE), silk plain weaves were already advanced, woven into gauzes and smooth fabrics. Silk served everyday needs for those who could afford it, but also functioned as tribute and diplomacy. Bolts of plain-weave silk were exchanged as currency, given to soldiers as pay, and sent abroad as luxury exports. As sericulture spread to Korea and Japan, the plain weave remained the foundation of East Asian silk traditions. What flax was to Egypt, silk was to China: a plain-woven fabric with both practical and symbolic power.

Weaving arose independently in the Americas. On Peru’s coast, plain-weave cotton dates back to 2500 BCE; later, alpaca and llama wool joined the loom. In Andean civilizations, textiles were more valuable than gold. Plain-weave cloth served as tax and tribute, with fine qompi fabrics reserved for elites and religious offerings. In Mesoamerica, Maya backstrap weavers created plain-weave cotton decorated with brocade and ikat. Here, weaving was sacred — overseen by the goddess Ixchel — and textiles marked political power as much as they did daily necessity. Plain weave provided both the everyday tunic and the sacred gift.

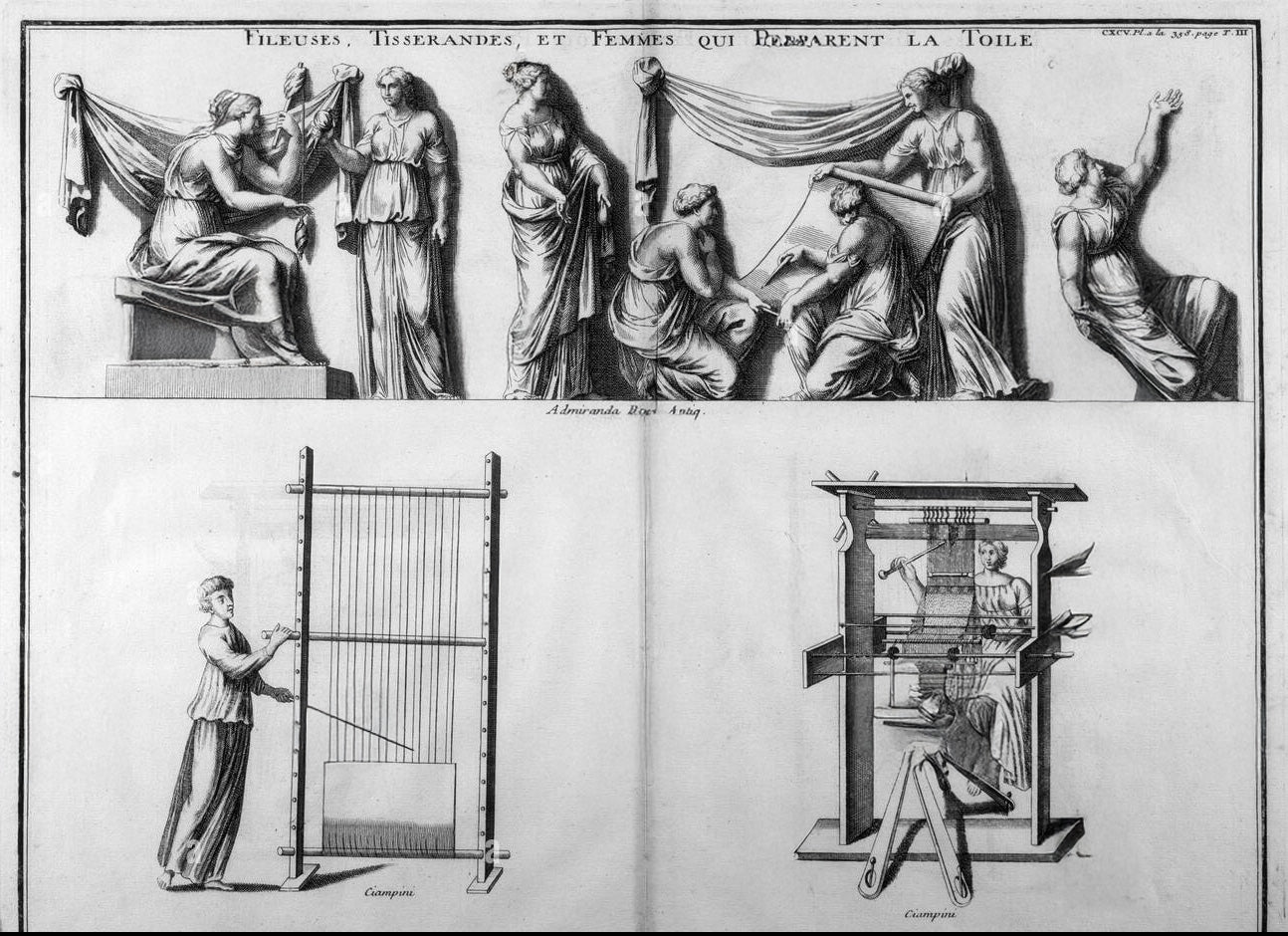

In prehistoric and classical Europe, plain-weave flax and wool provided shirts, tunics, and cloaks. Warp-weighted looms in Greece and northern Europe turned out balanced fabrics, sometimes patterned with checks or stripes. By Roman times, plain-weave linens and woolens were produced at workshop scale, supplying both local markets and long-distance trade. Everyday fabrics kept households clothed, while finer bleached linens and dyed wools signaled status. Cloth here was not only worn but traded, taxed, and regulated, making plain weave part of the economic backbone of Europe.

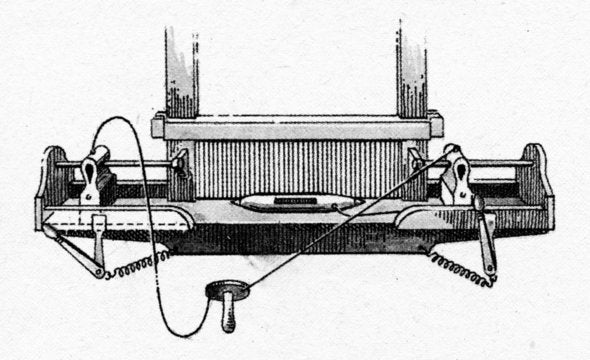

John Kay’s flying shuttle patented in 1733.

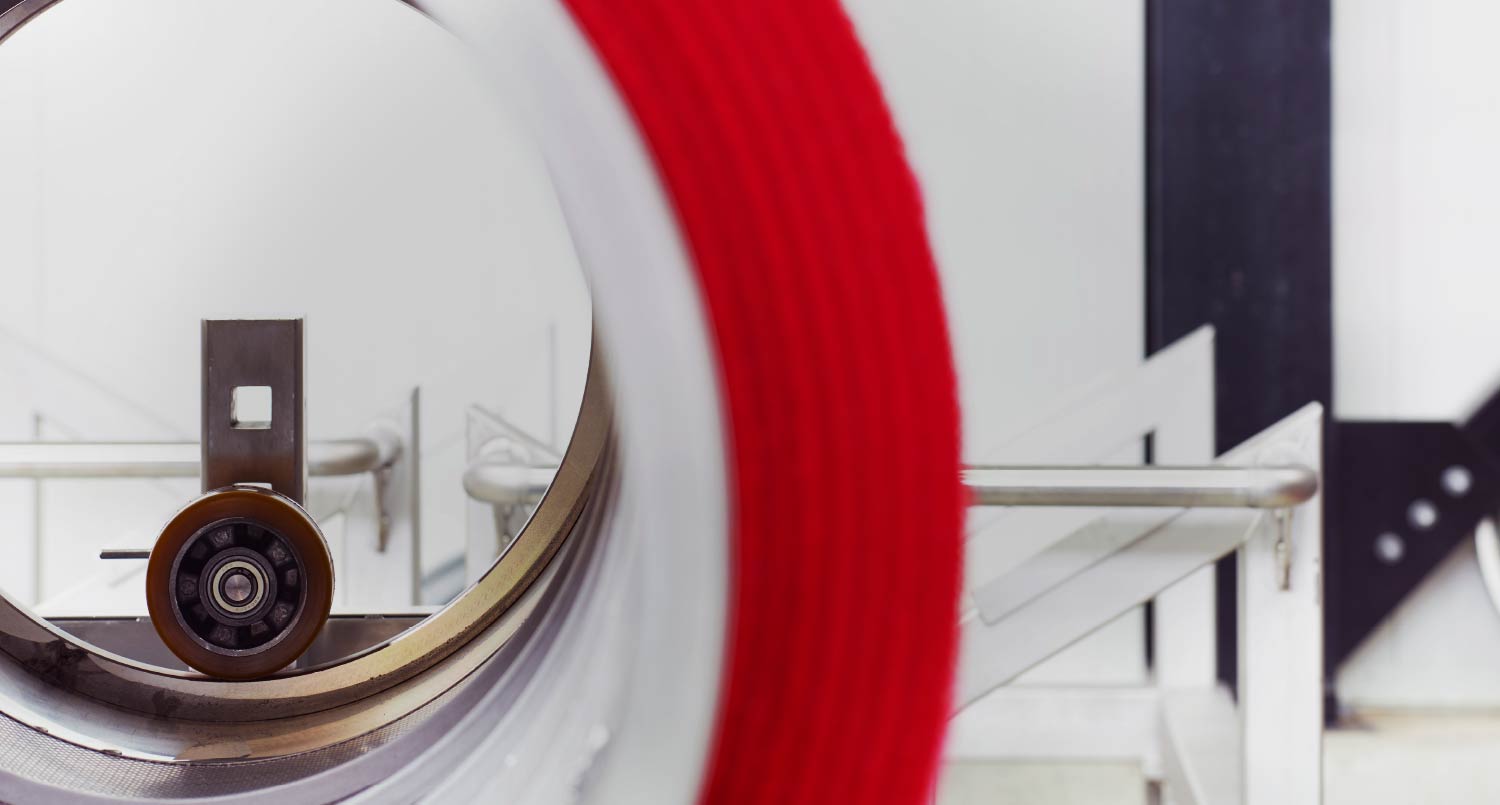

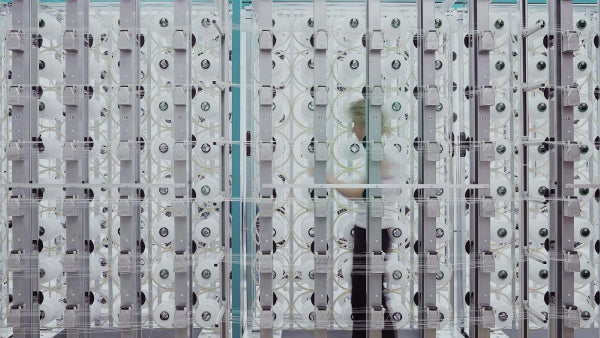

Early looms were simple: ground looms staked to the earth or upright warp-weighted looms with hanging stones. Both were efficient at making plain weaves. The addition of heddles and treadles allowed a single weaver to open sheds more quickly. By the medieval era, treadle looms in Europe and Asia enabled larger workshops and guild production.

The Industrial Revolution brought dramatic change. John Kay’s flying shuttle (1733) doubled speed. Edmund Cartwright’s power loom (1785) mechanized the process, driving the shift from household weaving to factory industry. By the 19th century, Lancashire mills were producing plain-weave cotton shirtings at unimaginable volume.

The Jacquard loom (1804) automated pattern weaving using punch cards — a precursor to computing. Though designed for complex weaves, it still built on the same warp-and-weft logic of plain weave.

Industrialization brought conflict as well. Displaced hand weavers protested, leading to the Luddite uprisings of 1811–13. But mechanization prevailed, democratizing access to textiles while reshaping economies from India to Egypt.

Plain weaving today is an industrial process, using computerization and automation for precision and efficiency.

Today, plain weave surrounds us in ways both familiar and unexpected. It’s there in the crisp cotton of a dress shirt, the lightness of silk chiffon, the texture of linen canvas, and the warmth of wool broadcloth. Its balanced structure makes it an easy canvas for printing, dyeing, and embellishment, which is why it has been a staple in wardrobes and homes for centuries. Yet the same over-under grid also underpins some of the most advanced materials of the modern world — the Kevlar layers in protective armor, the carbon fiber panels in aircraft, the ripstop nylon of outdoor gear. In many places, it continues to carry cultural meaning as well: in the patterned kasuri of Japan, the tartans of Scotland, the vibrant strip cloths of West Africa, or the handwoven cotton of Guatemalan backstrap looms. Designers, too, keep finding new possibilities. The Bauhaus weavers of the 1920s experimented with metallic threads and fiberglass, and today’s innovators are weaving conductive yarns into plain structures to create fabrics that can sense and respond. Across fashion, technology, tradition, and design, plain weave proves again and again that the simplest structure is often the most adaptable

Model of plain woven linens used as sails in Ancient Egypt.

The history of plain weave is the history of textiles. It clothed farmers in Mesopotamia, wrapped mummies in Egypt, powered sails across oceans, fueled colonial economies, and now strengthens aerospace panels. Its simplicity is its genius: one over, one under, repeated endlessly.

From flax by the Nile to carbon fiber in aerospace labs, plain weave is the unbroken thread connecting ancient craft to modern innovation. A fabric so fundamental it seems invisible, yet so enduring it continues to shape how we live, dress, and design.