Rugby shirts started in the mud. Originally made for 19th-century English rugby — a game that combines strategy, violence, and no padding — they were designed to survive impact. Heavyweight cotton, reinforced plackets, durable collars, and stripes for team ID. By the 1960s, climbers were facing their own version of punishment: sharp granite, coarse gritstone, rope drag, sun, and gear that cut or tore through soft layers. Rugby shirts made the leap from sport to stone because they could handle it — and they stuck around.

Functional Construction

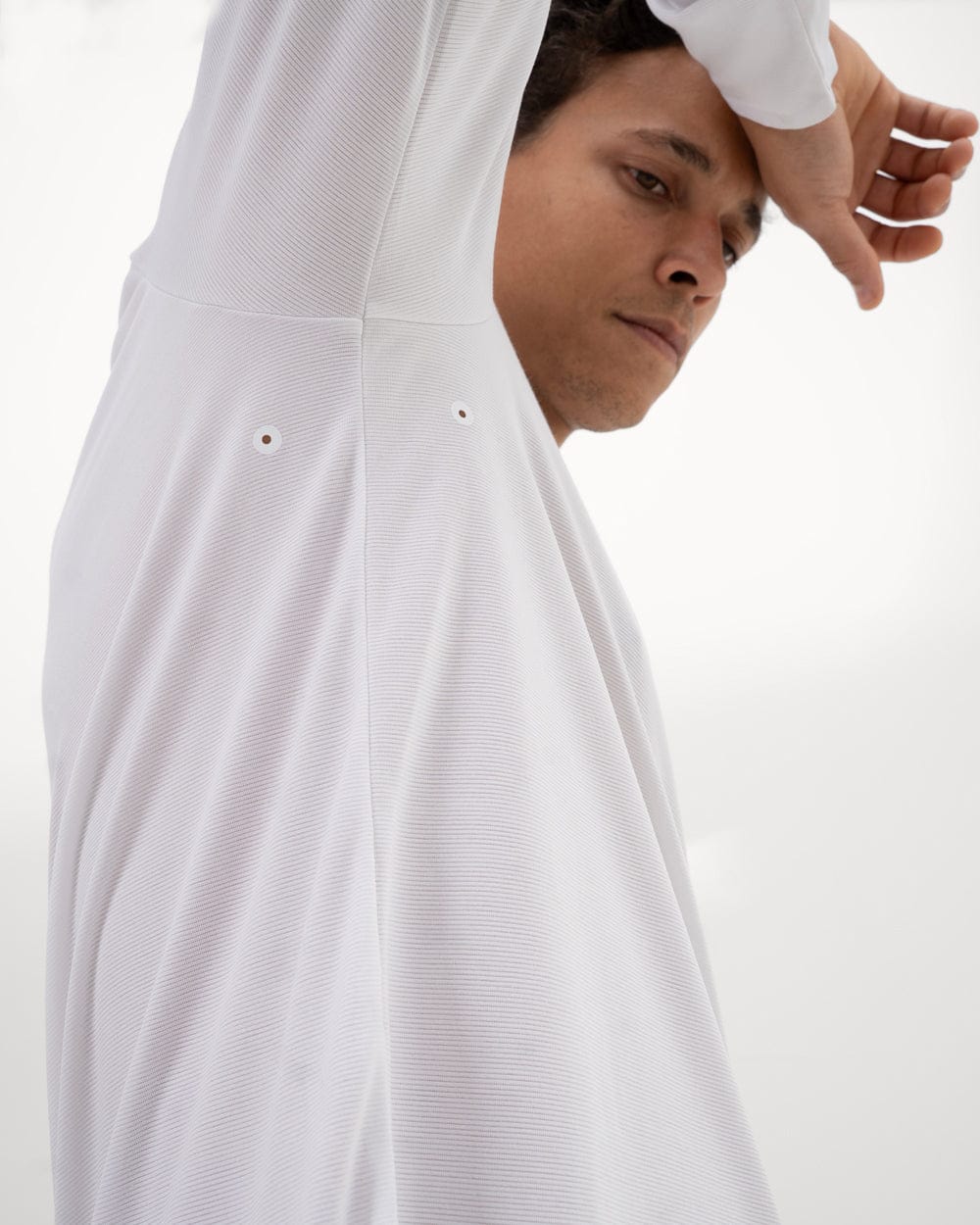

Rugby shirts weren’t breathable. They weren’t stretchy. But they were built to last. Made from 12 to 14 oz cotton jersey, they could take a beating — soft enough for all-day wear in the rain, tough enough to survive tackles or granite. Twill collars protected against sun and abrasion. Reinforced plackets with rubber buttons held up to constant pulling. Ribbed cuffs stayed put mid-route. Split hems kept the shirt from bunching under a harness. Climbers didn’t wear them for performance — they wore them because they worked. Over time, that function-first design turned into something else entirely: an accidental icon.

Inside the Fabric

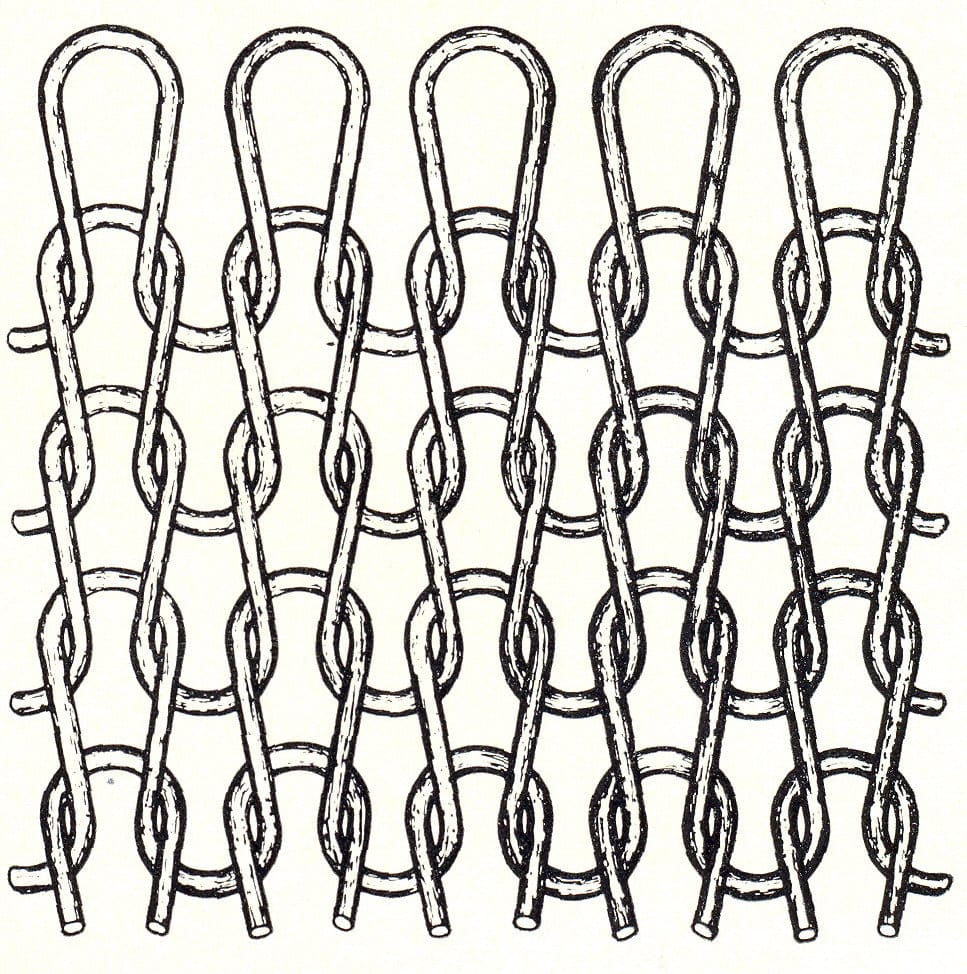

This simple loop structure is the foundation of single jersey fabric. Made with a single set of needles, it forms vertical knit stitches on the front and horizontal purl loops on the back.

Most rugby shirts use single jersey knit — one of the simplest and most versatile knit constructions in textiles. It’s made using a single needle bed on a circular knitting machine, producing fabric with distinct front and back sides. The front (or “right side”) shows smooth vertical knit columns that resemble tiny V’s, while the back reveals horizontal loops or “purls” that give the fabric texture and depth.

This structure creates a unique stretch profile: more give side-to-side than top-to-bottom. That lateral flexibility makes rugby shirts comfortable to move in — especially when climbing, reaching, or jamming into cracks — while the vertical stability keeps the garment’s shape intact after years of wear.

On heavyweight versions, like the 12 to 14 oz cotton used in traditional rugby shirts, the interior is often brushed — softening the purl loops and giving the shirt that broken-in feel right out of the box. It’s what makes a good rugby shirt feel almost pre-worn — sturdy on the outside, soft against the skin.

And because it’s a single knit layer (as opposed to double jersey or fleece), it maintains better airflow and dries faster than you’d expect from thick cotton — not technical, but functional in a very real, very analog way.

Not Just Nostalgia

Rugby shirts were never meant for climbing — and maybe that’s exactly why they worked. Their bold stripes, once meant to tell teams apart, became a kind of cultural shorthand: not technical, not flashy, just confident. British climbers in the 1950s and ’60s wore them because they were tough and available, often pulled from university kits. In the 1970s, they became part of the Yosemite identity — a signature of climbers who made them look effortless on granite walls. Even Patagonia, in its Chouinard Equipment days, understood the vibe. By the late ’70s, rugby shirts were in the catalog . They weren’t performance wear, but they belonged. Thick cotton, stitched tight, built for impact. The rugby shirt outlasted trends and quietly earned its place in climbing history.

It wasn’t technical. But it was honest.