How Down Became Performance Gear: From Arctic Survival to Altitude and War

Down insulation is now a staple of high-performance outerwear — known for its warmth, light weight, and compressibility. But its origins run much deeper than modern mountaineering or technical design. This article traces the evolution of down from its early use by Indigenous Arctic communities, to George Finch’s pioneering Everest suit, to Eddie Bauer’s mass adoption through WWII. It’s a story of survival, experimentation, and the transformation of natural loft into engineered insulation.

Indigenous Origins of Down Insulation

The common eider duck (Somateria mollissima) is a large sea duck native to Arctic and sub-Arctic coastal regions. These birds nest in colonies, and their down — soft plumage from the breast — is plucked by the ducks themselves to line their nests and keep eggs warm. This down is exceptionally fine and has a unique clingy structure, allowing it to trap heat efficiently. Arctic communities recognized this natural insulation and developed sustainable methods to collect it.

In areas like Iceland and Greenland, eider down was — and still is — gathered by carefully removing it from vacated nests without harming the birds. Some Indigenous groups used similar methods, valuing the material for its warmth, loft, and lightness. The Inuit and Kalaallit (Greenlandic Inuit), in particular, used entire eider skins with the down still attached. These were sewn into coats, mittens, trousers, and bedding — garments that could be worn feather-side-in for warmth or feather-side-out for weatherproofing and water resistance.

These garments weren’t improvised or crude. They were carefully designed systems, engineered for survival in climates where wind chill, wetness, and prolonged cold could be deadly. Down-insulated layers were often paired with other materials, such as caribou hide or seal skin, each selected for specific functional roles like waterproofing, wind-blocking, or breathability.

Eider-down clothing was particularly valuable in regions where caribou was scarce or where greater mobility was required, such as in kayaking or hunting on foot. The garments were lightweight, compressible, and incredibly warm — essential for maintaining body heat without limiting movement. Danish explorer Hinrich Rink once described eider duck skin garments as “lighter and warmer than any European clothing,” noting their use as both daily wear and specialized sleeping layers.

Franz Boas and other early ethnographers documented these garments in detail, often noting how much more effective they were than the wool and canvas used by European traders and explorers. These observations weren’t romanticized admiration — they were practical comparisons from people who had worn both.

This use of down reflected a deep ecological and material intelligence. Indigenous knowledge systems included careful instruction on where and when to gather down, how to dry and preserve it to retain loft, and which types of bird skin worked best for different purposes or seasons. Feathered garments were reversible, modular, and adaptable, showing a level of material literacy that rivaled — and in many ways exceeded — later Western technical apparel.

Though the modern down jacket is often credited to George Finch in the 1920s or Eddie Bauer in the 1930s, the functional idea of using down as active insulation began much earlier. Arctic communities had already demonstrated the warmth-to-weight ratio of down, developed methods to contain and optimize loft, and pioneered systems of layering and moisture management. These weren’t experiments — they were proven systems refined over centuries.

George Finch and the Down Jacket

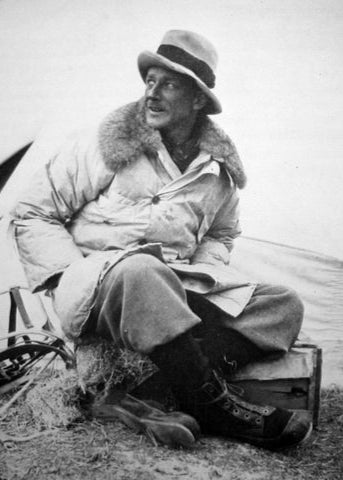

George Finch was an Australian chemist and mountaineer, recruited to the second British Everest expedition not just for his strength, but for his deep interest in the science of survival at altitude. Where others trusted tradition, Finch trusted experimentation. He arrived in base camp not only with oxygen apparatus of his own design, but with the first purpose-built down climbing suit in history. It was shocking to look at — bright green, balloon fabric, bulky. A complete departure from the wool, gabardine, and silk layers worn by the rest of the team.

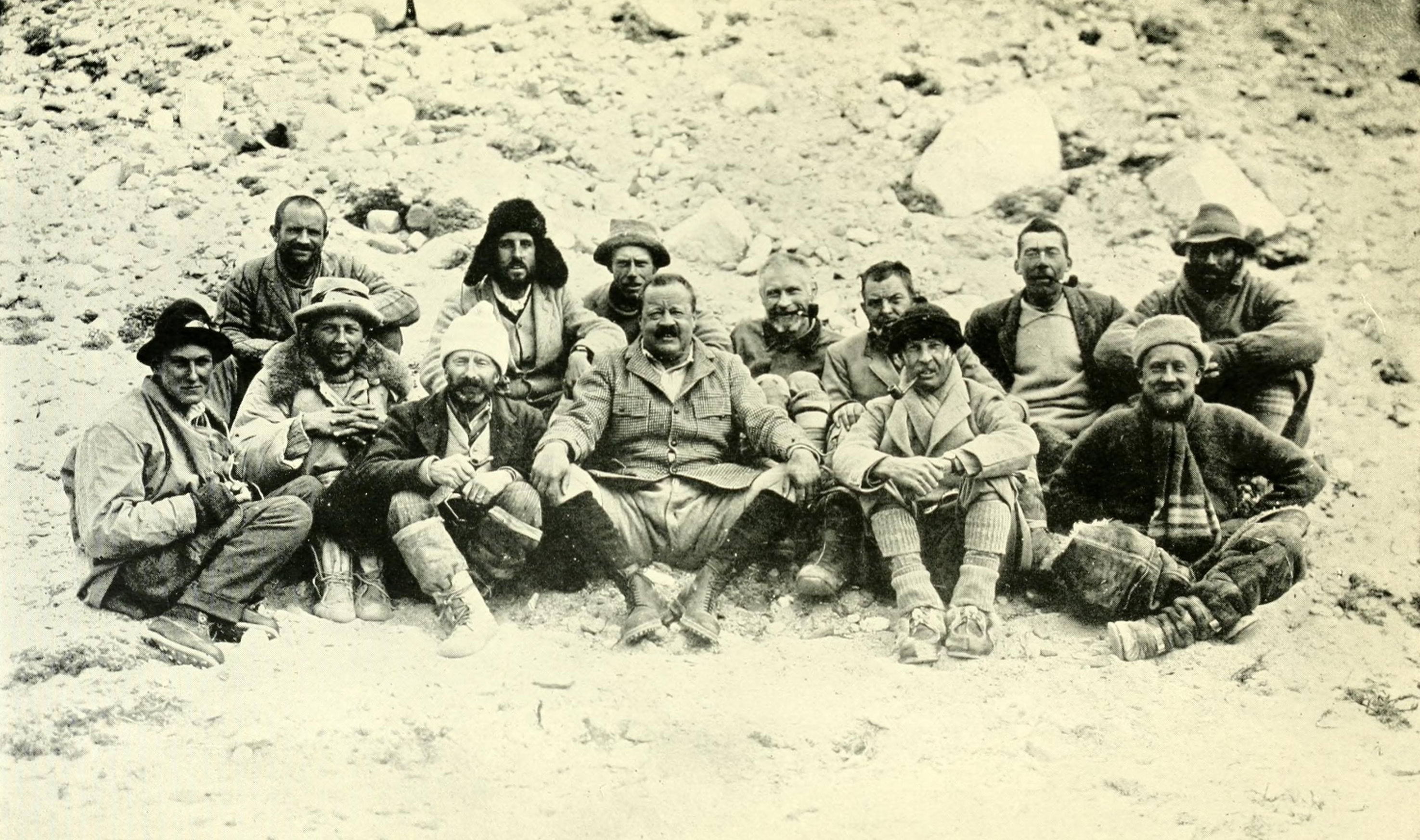

1922 British Mount Everest expedition, George Ingle Finch is front row, second from left. The expedition was notable for achieving a new altitude record at the time and for the use of oxygen in their ascent attempts. George Finch and Geoffrey Bruce reached an altitude of 27,300 feet (8,320 meters) using oxygen.The expedition's main goal was to make the first ascent of Mount Everest.

Finch’s down jacket and trousers were constructed from surplus balloon fabric — a tightly woven, rubberized cotton used in hot-air balloons — which made them windproof and somewhat water-resistant. Inside, the suit was filled with high-quality eiderdown, chosen for its exceptional loft and insulating properties. He essentially created a mobile sleeping bag, decades before the world would come to see that as smart.

This was radical for the time. Traditional mountaineering attire was built on a layering system of natural fibers: merino base layers, wool mid-layers, and tightly woven outer layers made from gabardine or ventile. While these materials had their strengths, they also absorbed moisture, were heavy when wet, and lost insulative power at high altitude. Finch’s suit, by contrast, was lightweight, trapped heat effectively, and retained loft even in thin, frozen air.

What Finch designed in 1922 — a wearable, wind-resistant shell filled with eiderdown — was entirely new to the European mountaineering world. But the core idea had already existed for centuries among Indigenous Arctic communities.

In Finch’s journals and post-expedition commentary, he noted how the suit created a warm microclimate — one that allowed him to eat, breathe, and think more clearly than those dressed in traditional gear. Even the team’s expedition doctor, initially skeptical, conceded that the suit had offered a real physiological advantage.

Despite its success, Finch’s gear was dismissed by many in the British climbing establishment. The coat didn’t look the part. It wasn’t traditional. It was too bright, too strange, too un-British. Finch himself was seen as an outsider: Australian, outspoken, and critical of the expedition leadership. After the climb, his technical contributions were downplayed or ignored in official reports.

But among those who understood what mattered — staying warm, staying alive — Finch’s innovation was unforgettable.

WWII & Eddie Bauer

Before down became standard military issue, bomber crews flying in unpressurized aircraft at high altitudes relied on heavy leather flight suits — often the Type A-2 leather jacket or shearling-lined variants like the B-3. These garments, designed in the 1930s, were based more on durability and protection than thermal performance. The B-3 bomber jacket, for example, used thick sheepskin and heavy-duty zippers to protect pilots from subzero temperatures. But these materials had serious limitations.

Leather, while tough, absorbed moisture and could become stiff or even freeze at altitude. Shearling added warmth, but also bulk and inflexibility. The gear was heavy, cumbersome, and performed poorly in sustained exposure. Pilots layered wool beneath their outerwear — sweaters, long johns, and multiple pairs of socks — but the system was inefficient. At 25,r000 to 30,000 feet, temperatures routinely dropped below -40°C. Frostbite, impaired motor function, and even death from exposure were real risks. The U.S. Army Air Forces knew they needed something warmer, lighter, and more functional.

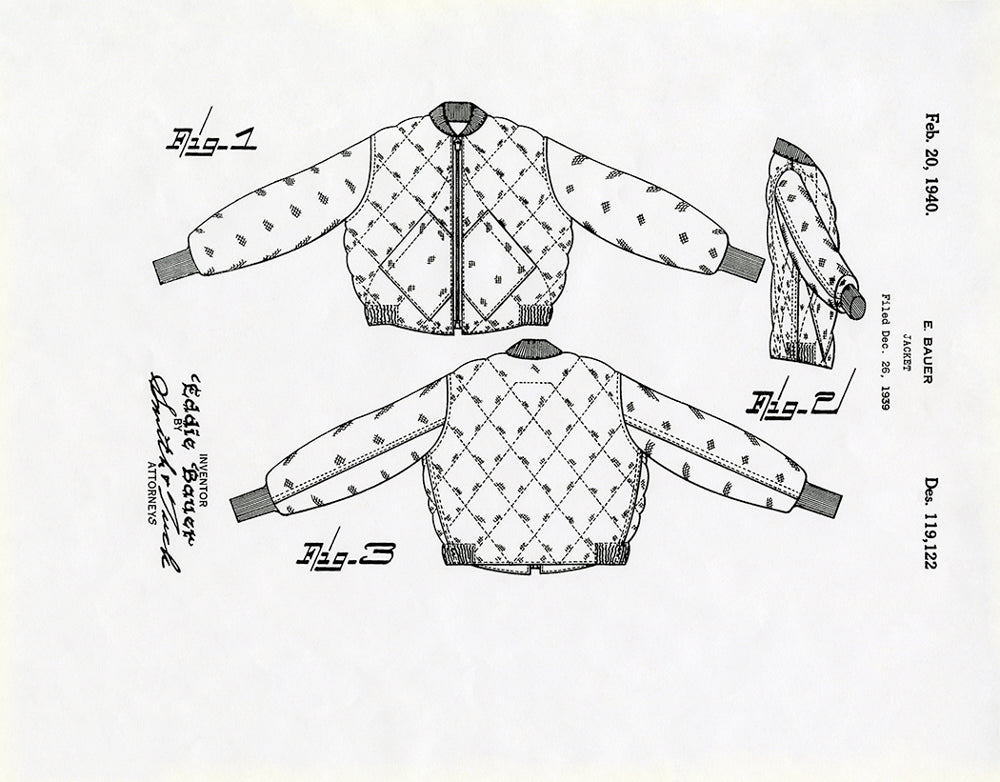

Eddie Bauer’s initial innovation was the invention of the quilted down jacket, which used sewn-through baffles to keep the down evenly distributed and prevent it from shifting or clumping. This technique preserved loft and ensured consistent warmth across the body. In 1940, Bauer patented his design: the Skyliner Jacket, the first commercially available down-filled garment in the United States. It weighed far less than a comparable wool coat, packed smaller, and retained more heat — especially in dry, cold environments.

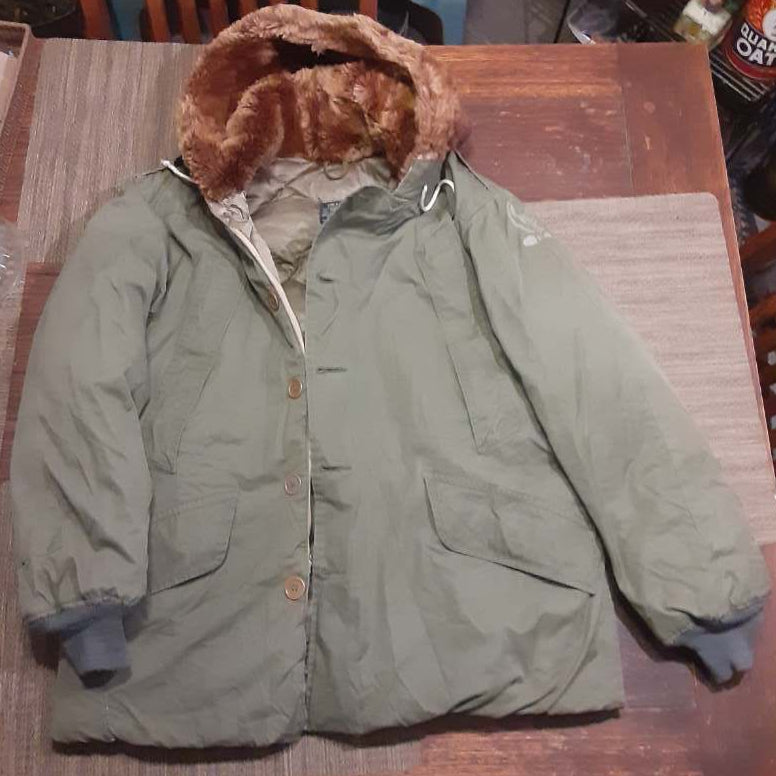

But when WWII broke out, Bauer was hired by the military supply chain to develop cold-weather gear for bomber crews. The result was the B-9 Parka, paired with the matching A-8 flight trousers. The B-9 featured a windproof cotton shell, a fur-lined hood, and a down-filled interior organized into quilted baffles. These garments used high-quality goose down as the insulating medium, offering superior warmth-to-weight performance compared to shearling. The jackets allowed for better range of motion in tight cockpits, dried faster, and weighed significantly less than the wool-and-leather systems they replaced. Strategic baffling prevented cold spots. The garments were designed to integrate with layered flight gear, and their streamlined silhouette made them practical for both aviation and on-the-ground use.

By the end of the war, Bauer’s designs had been adopted widely. Over 50,000 B-9 parkas were produced for the military. Soldiers and airmen praised the gear for keeping them alive in the harshest altitudes and cold-weather theaters — from the European air war to Arctic outposts.

Why It Mattered

The wartime collaboration between the U.S. military and Eddie Bauer did more than solve a logistical problem — it industrialized down insulation and use. Bauer took a material previously associated with bedding and transformed it into a technical, scalable, field-tested system for survival.

The quilted baffling, the focus on fill retention, the use of windproof outer shells — all these innovations laid the groundwork for modern down garments. Finch’s 1922 suit proved what was possible. Bauer proved it could be done at scale. And beneath both was a principle Indigenous Arctic communities had known all along: when trapped properly, down is one of nature’s most efficient insulators.

The technology advanced. The structure changed. But the core idea endured — and this takes us generally to where we are today with the application of down insulations.