Durable Water Repellent (DWR) coatings are the invisible shield that make water bead and roll off your garments — a small detail that plays a big role in keeping your gear breathable and lightweight. But beneath the surface of those satisfying water droplets lies a deeper story: one that spans decades of chemical innovation, growing environmental concern, and a complete rethinking of how performance gear is made.

This is a look at how DWR evolved, why it’s changing, and what comes next.

From Waxed Cotton to Fluorocarbons

The search for water-resistant clothing goes back over a century. Early methods — waxed cotton, alum treatments, or Cravenette finishes — worked, but came with obvious limitations: they weren’t breathable, often felt heavy, and needed frequent reapplication. A breakthrough came in the mid-20th century, when chemists discovered that applying long-chain fluorocarbon polymers to fabric could repel both water and oil more effectively than anything before. These new synthetic coatings weren’t just water-resistant — they created a nearly frictionless surface that made liquid slide off instantly.

By the 1970s, this chemistry had found its way into high-performance outdoor gear. Gore-Tex and other early waterproof-breathable membranes relied on these fluorinated finishes to prevent the outer fabric from saturating with water. This outer layer — treated with what came to be known as DWR — helped maintain breathability by keeping rain from soaking into the fabric.

The C8 Era

For decades, the most common DWR treatment relied on what's known as C8 chemistry — short for an 8-carbon perfluorinated chain. These coatings were built around compounds like PFOA and PFOS and quickly became the industry standard. They offered unmatched water repellency and also resisted oils, stains, and dirt — a dream for outdoor apparel. But while these long-chain PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) performed beautifully on fabric, they also proved incredibly persistent in the environment. Over time, scientists began finding traces of C8 chemicals in soil, water, and even human blood. These compounds can remain in soil, water, and living systems for decades or longer. One of the most significant studies, the C8 Health Project, followed over 70,000 people exposed to PFOA in West Virginia — and linked the chemical to a number of health issues, including kidney and testicular cancer, thyroid disruption, and immune suppression.

For the outdoor industry, this created a direct contradiction: the gear built to explore and protect the natural world is contributing to long-term pollution and health concerns.

C8 to C6 to Elimination

In response to deep concern over C8 exposure, the industry shifted to C6-based chemistries. These shorter-chain PFAS compounds were believed to be less bioaccumulative, while still offering strong water repellency. C6 became a popular drop-in replacement for C8, giving brands a way to maintain performance without the public scrutiny. But C6 came with its own problems. While it may accumulate less in living organisms, it's still a PFAS — still persistent, still synthetic, and still showing up in ecosystems where it doesn’t belong. Over time, it became clear that C6 was a not a solution. The focus began to shift from managing risk to eliminating fluorinated chemicals altogether.

In the United States, California and Minnesota are leading the way in passing legislation to force change. California has banned the sale of apparel containing intentionally added PFAS starting in 2025. Minnesota has passed even broader restrictions, covering everything from cookware to ski wax. The message is clear: if your product contains PFAS, it soon won’t be allowed on store shelves. Alongside legislation, reputational risk is also rising. Lawsuits have targeted major brands and suppliers for PFAS contamination, and chemical companies like 3M and Chemours are facing massive settlements.

The writing is on the wall: the age of PFAS is ending.

What Comes Next

With the pressure to move on from PFAS, brands are now exploring a wave of fluorine-free alternatives. These new DWR technologies aim to deliver similar performance without the long-term harm.

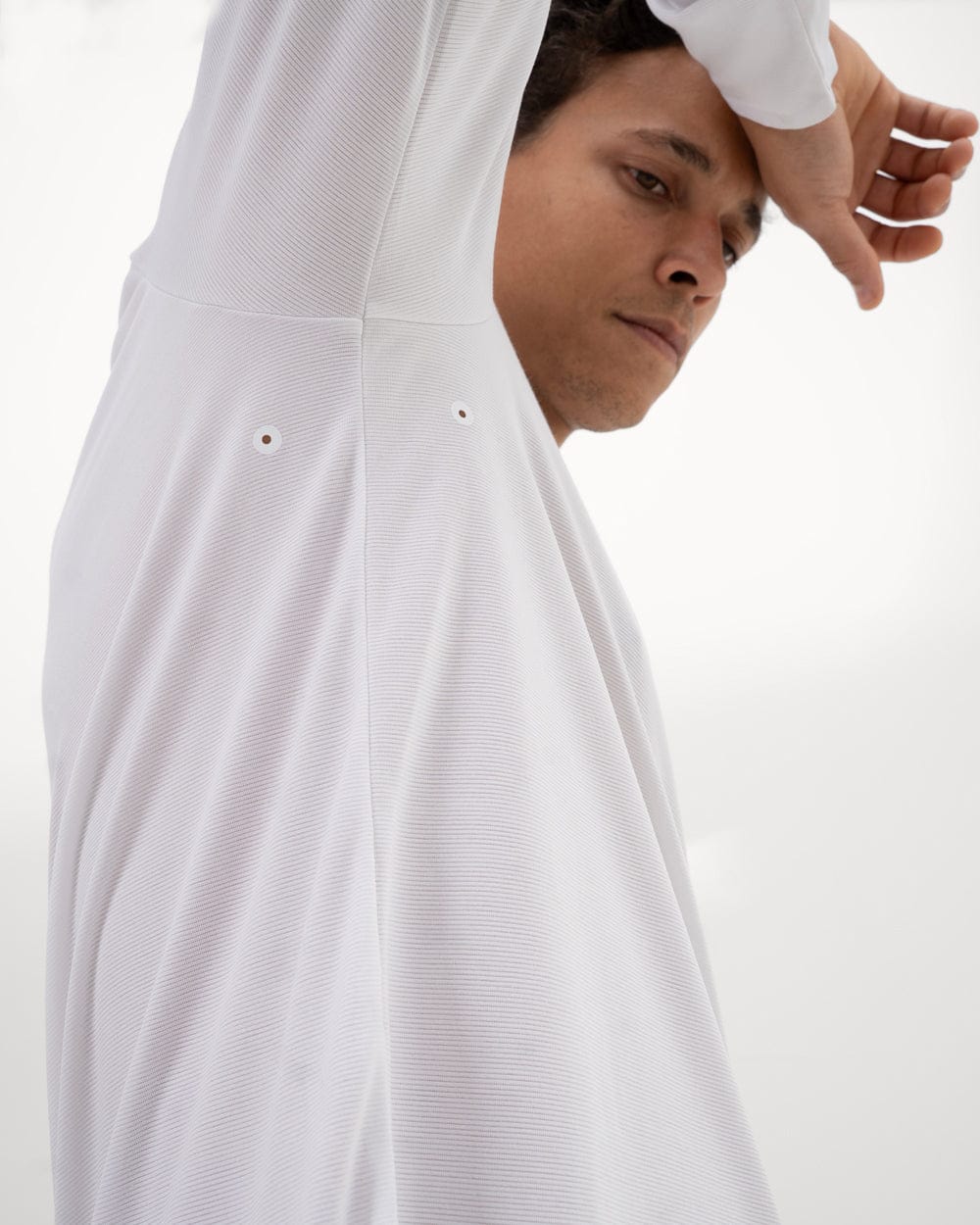

One such innovation is wax- and hydrocarbon-based finishes. For example, Foehn partners with Schoeller® to use ecorepel®, a finish made from biodegradable paraffin wax. Inspired by natural oils found in animal fur, it repels water effectively in light to moderate rain and is completely fluorine-free. While it may not resist oil-based stains as well, it offers excellent breathability and is easily renewable with heat.

There’s also growing interest in bio-based DWR treatments, which use plant-derived ingredients like corn sugar or fatty acids to create a hydrophobic surface. These coatings are made from renewable resources, perform well in dry conditions, and align with broader goals around circularity and low-impact manufacturing.

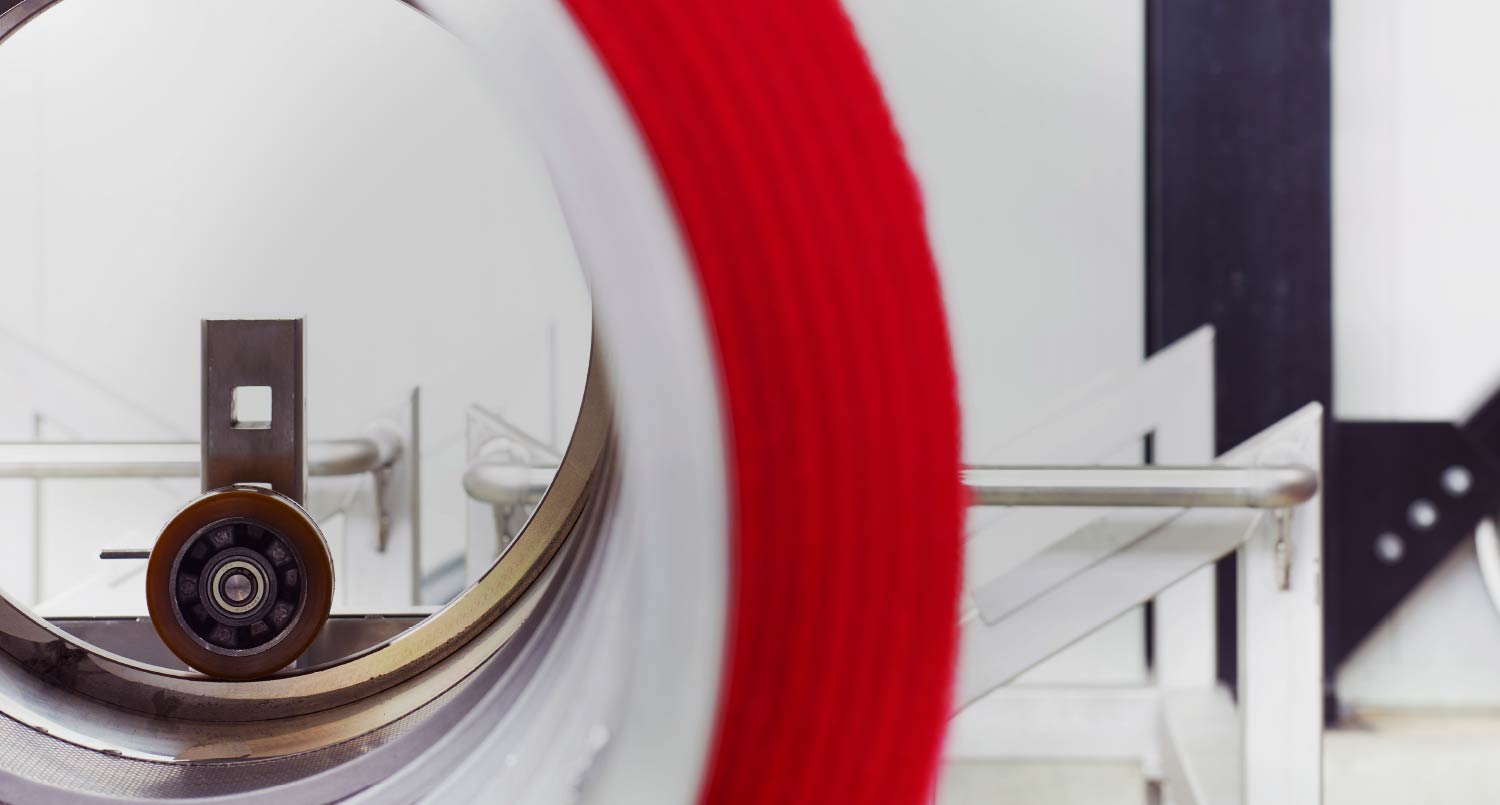

Some companies are going even further, exploring dry application methods like plasma treatment or chemical vapor deposition. These techniques use vacuum chambers or ionized gas to bond water-repellent compounds directly to fabric fibers — reducing chemical waste and improving durability without liquid baths.

Performance Tradeoffs

In many ways the new C0 DWR finishes are remarkably close to to their predecessors — especially in water repellency. When new, most fluorine-free treatments will bead water effectively. In prolonged, heavy rain, performance might drop off a little faster than with C6 or C8, but the difference is narrowing with each generation of innovation.

Durability is where PFAS still hold an edge. Fluorinated finishes tend to last longer through abrasion and multiple washes. Fluorine-free DWRs may require more frequent reactivation — usually via heat (a tumble dry or iron) — to maintain performance.

Additionally where fluorine-free treatments fall short is oil and stain resistance. Without PFAS, there’s no oleophobic barrier — meaning sunscreen, body oils, or greasy stains can more easily penetrate the fabric and degrade the DWR in those areas. This doesn’t affect all users, but it’s something to be aware of, especially for gear exposed to regular skin contact or environmental grime.

The Bottom Line

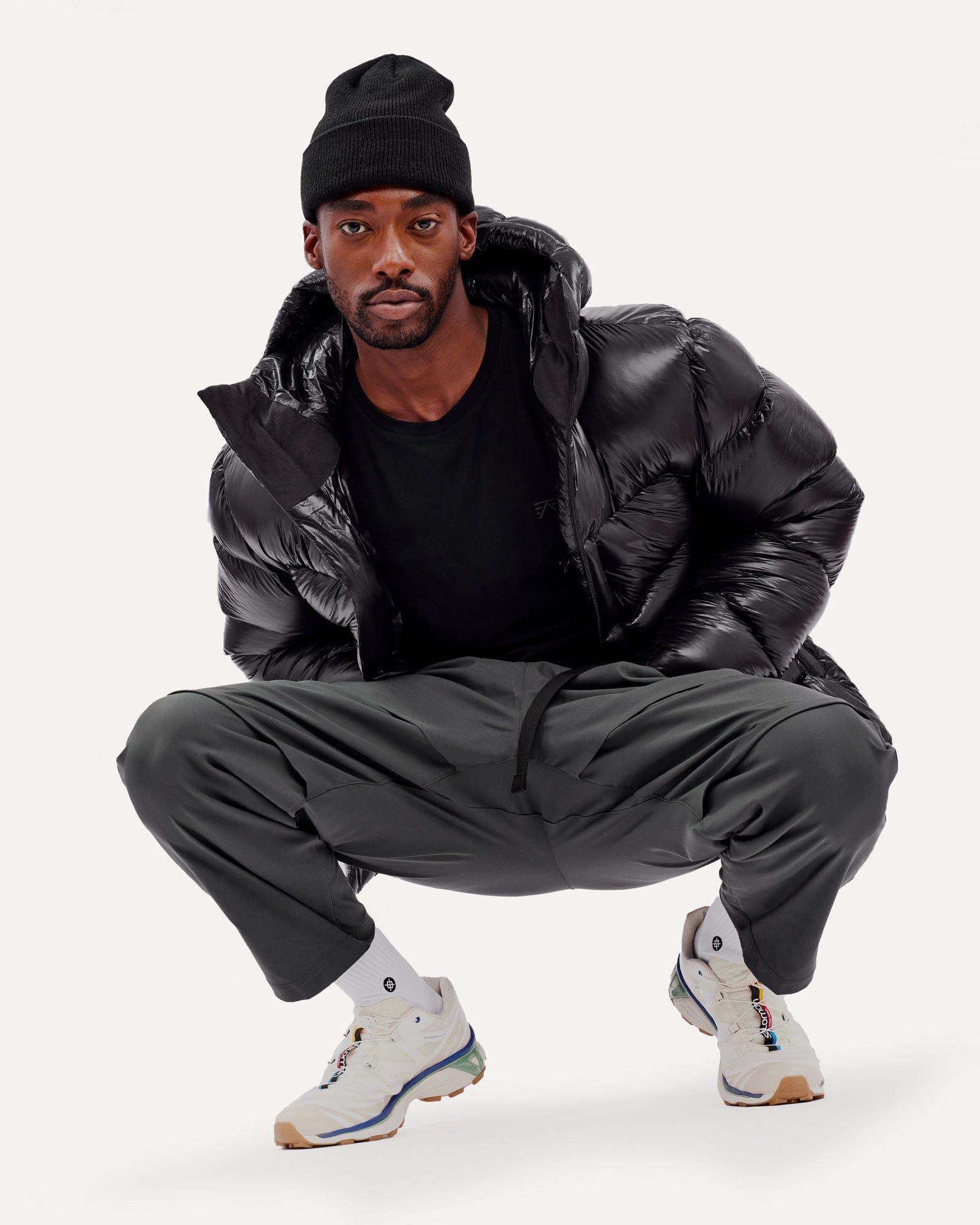

Fluorinated DWR finishes set a high bar for performance. But that performance came with a cost — one that’s no longer acceptable. Today’s fluorine-free finishes offer real-world function for most outdoor conditions and a dramatically reduced environmental footprint.

At Foehn, we’ve committed to this shift by working with partners like Schoeller® to develop high-performing, PFAS-free gear. Because innovation doesn’t mean compromising performance — it means rethinking how we get there.