If you’ve clipped into a climbing sling, packed an ultralight bag, or watched a sailboat cut against the wind, you’ve already trusted Dyneema® — whether you knew it or not. The thin, waxy-looking fiber is 15 times stronger than steel by weight, completely hydrophobic, and so light it floats. It’s changed how we design outdoor gear, but its story started far from the mountains.

What Is Dyneema®?

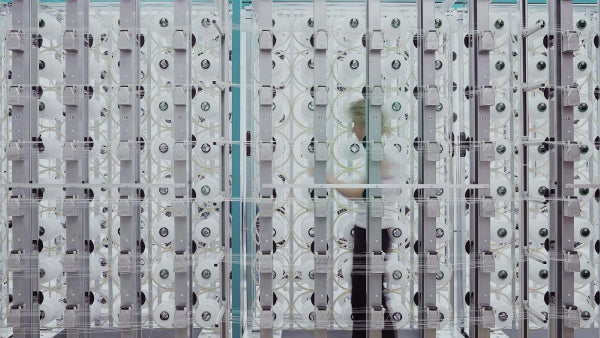

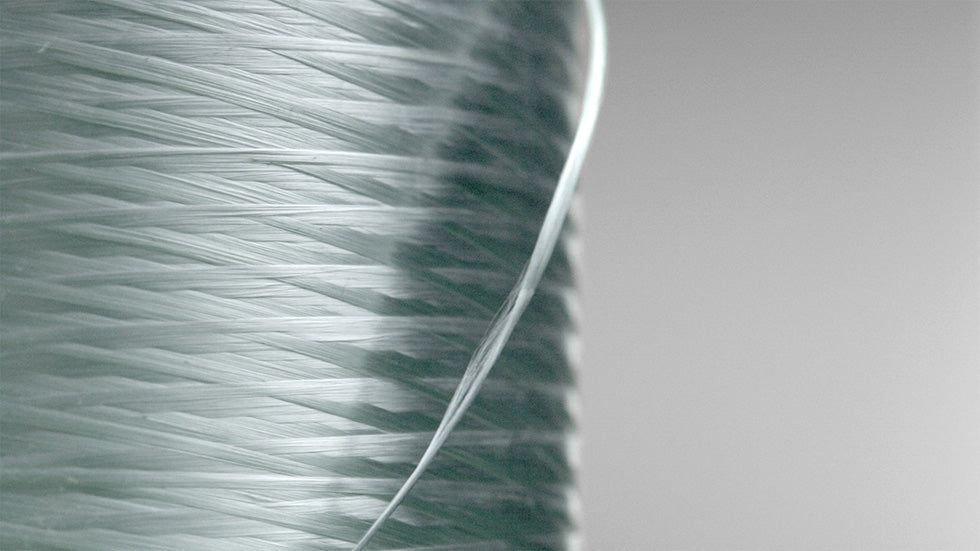

Dyneema® is the trade name for Ultra-High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) — polyethylene pushed to its absolute limits. Unlike standard polyethylene, which is a loose tangle of short molecular chains, Dyneema® is made through a gel-spinning process that stretches and aligns those chains into long, highly ordered structures. That alignment is the key: instead of breaking under stress, the fibers distribute force evenly, making them exceptionally strong for their weight.

It’s resistant to cutting and abrasion, absorbs no water, and has almost no stretch under load. Stronger than steel by weight, lighter than water, and unusually durable for its size, Dyneema® shows up anywhere failure isn’t an option — rescue ropes, ballistic armor, and, increasingly, outdoor

From Lab Accident to Ultralight Gear

The first Dyneema® fibers were made in 1979 by researchers at DSM (Dutch State Mines), who discovered that polyethylene behaved very differently when stretched under the right conditions. Its early applications were industrial: tow cables, mooring lines, and body armor. Climbers were next. By the 1990s, Dyneema® webbing began replacing nylon slings. It wasn’t perfect — its low stretch made it unsuitable for dynamic climbing ropes — but it was lighter, thinner, and far more cut-resistant.

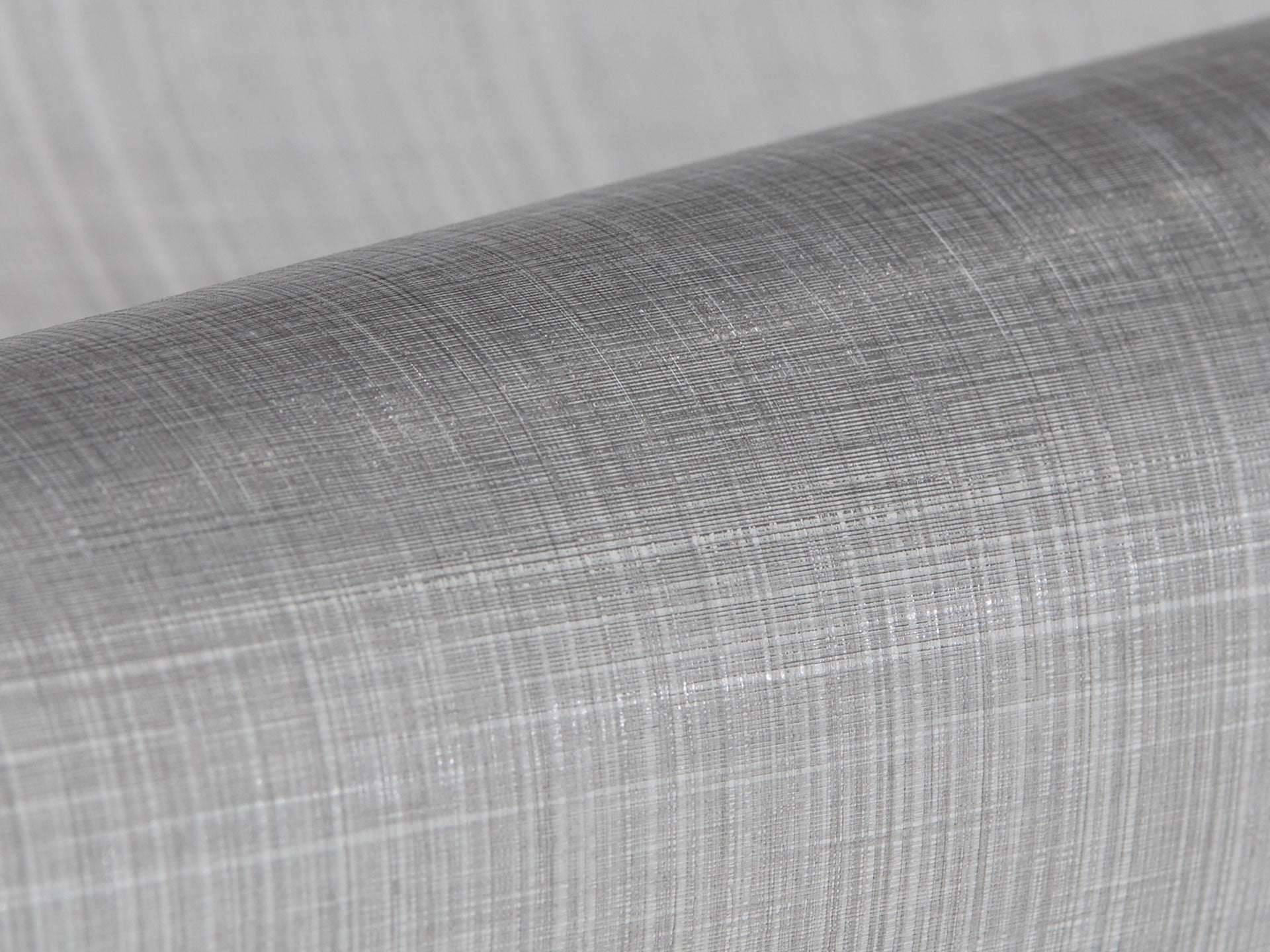

The real shift came in the 2010s with Dyneema® Composite Fabric (DCF), originally developed for racing sailboats. By sandwiching Dyneema® fibers between ultra-thin films, DCF delivered a waterproof, incredibly strong, and dramatically lighter alternative to woven fabrics. Ultralight hikers embraced it first, and it reshaped pack and shelter design almost overnight. Dyneema® allowed strength without bulk, making gear that was once heavy and overbuilt suddenly lighter, simpler, and faster. Climbers carried slimmer slings, hikers hauled shelters that weighed a fraction of traditional ones, and a new philosophy of movement — counting grams, traveling farther with less — took hold.

The Fine Print

For all its advantages, Dyneema® isn’t flawless. Its low melting point (around 145°C) makes it vulnerable to friction heat. Long-term tension can cause creep, a slow, permanent deformation. UV light degrades it over time unless coated or blended with other materials. And while it’s efficient in use, it’s expensive to produce and still petrochemical-based.

There are changes coming. DSM recently launched a bio-based Dyneema® made with 75% plant-derived carbon, which performs identically but carries a lower carbon footprint. Recycling remains a challenge, though chemical recycling projects are being explored as the outdoor industry pushes toward circular design.

More Than a Survival Material

What began as a purely functional material has become a symbol of a different way of thinking about the outdoors. Ultralight packs and shelters built from Dyneema® have become shorthand for efficiency and intent — gear stripped down to exactly what’s needed and nothing more.

Dyneema® didn’t just make equipment stronger; it changed how we think about weight and reliability. It let climbers carry less, hikers travel farther, and designers reduce gear to its essentials. It isn’t perfect — heat-sensitive, UV-sensitive, expensive — but no other fiber has done more to push outdoor gear into the ultralight era.